A Look at My Own Private Idaho

An in-depth analysis at several of the little cinematographic details, stylistic choices, and general visual observations that contribute to the meaning of this cult classic film.

A quick note from the author: This is a republished essay I wrote about three years ago, when I was sixteen. Some parts have been edited for clarity, but I’ve left most of it alone since at the time it was well-received from the community I shared it with. Frankly, it’s pretty long, more like three or four separate essays in a trench coat, but I honestly think it’s got some good stuff. It’s just here to have all my work in one place, so feel free to skip to whatever in this analysis interests you the most! I hope you enjoy :) — Brishti

What even is a “Private Idaho?”

The title of the film derives from the B-52s song, eponymously titled “Private Idaho.” In the song, the speaker details the subject’s delusions, and declares that they are living in their “own private Idaho.” As such, this “private Idaho” represents not necessarily a physical state, but cleverly, a state of mind, one far removed from the man-made constraints of society.

Gus Van Sant’s 1991 independent film My Own Private Idaho is something of an amalgamation in filmmaking. It was conceptualized as a combination of two distinct scripts, one being a story about impoverished young queer prostitutes on the streets of a major city, and the other being a modern retelling of Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Parts I and II. This is specifically highlighted in the contrasting yet unified stories of its leads: Mike Waters, a homeless teenage hustler affected by narcolepsy, played by the late River Phoenix, and Scott Favor, the son of Portland’s mayor due to inherit great wealth, played by a young Keanu Reeves.

Indeed, the film would later go on to be remembered as a staple in the New Queer Cinema movement of the 1990s — a collection of avant-garde filmmaking centering queer themes. This film revolves around the situations that entangle Mike and Scott, and the way they confront or deny their queer identities posed in the backdrop of several competing plots that strive towards a unified end. The story is a true adventure-drama traveling across the Northwestern United States, as it follows the characters in their journey as it starts in Idaho, moves to Seattle, and situates itself in Portland for quite some time before letting the characters appear in Idaho once more; from there, they travel to Rome, back to Portland, before once again landing in the very same Idaho road from the beginning.

In this analysis, I would like to look deeper at several elements that I feel define this film, from the themes of nature, escapism, and free will, to the costuming choices that I feel reflect these themes, to an exploration of sexuality — while answering some key questions fans of the movie have long debated along the way.

The Cinematography of the Opening

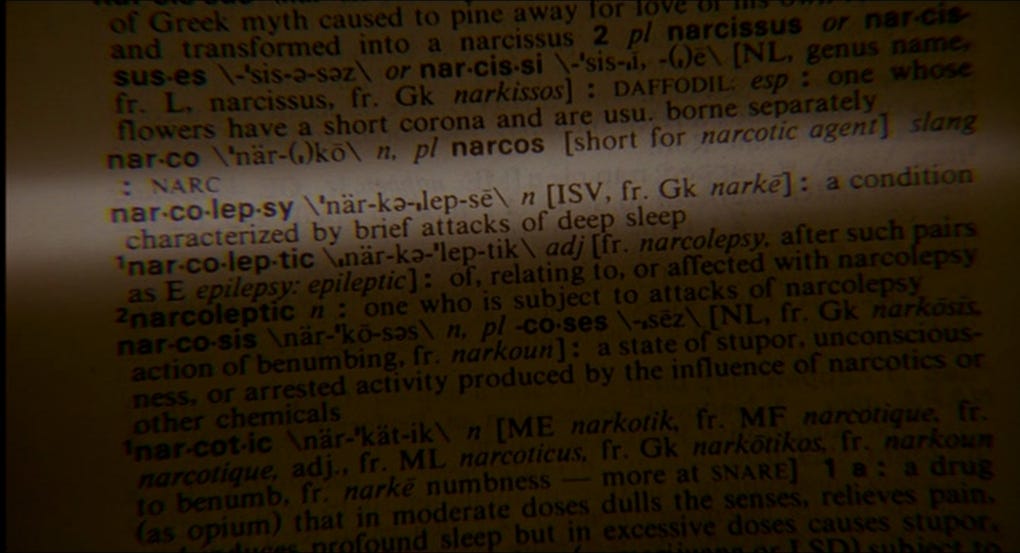

In My Own Private Idaho, the characters struggle with their role in a larger society, and often find solace in a natural setting, a place where they can escape the expectations imposed upon them. This natural setting is emphasized almost immediately within the film, with the opening shots hinting at this struggle between man-made impositions vs. the natural condition. The first shot of the movie is a dictionary definition of the word “narcolepsy.”

Through this, we’re immediately introduced to the conflict that Mike must endure throughout the film: his natural disability, one that he cannot control. His disability remains a natural part of who he is, and his struggles are a result of fate. Deceptively, the capitalistic society in the major cities offer him a facade of free will: he cannot choose to struggle with a disability, but he appears to have the choice to seek help. However, due to his homelessness and poverty, all options are eliminated, and he must continue to suffer without treatment. Within the framework of society, he is rejected, and cannot seek aid due to the constraints of his setting. As such, he is pushed to the margins of society, a force outside his free will.

The first true shot of the movie is a cut to a barren, Idaho road, right before our main protagonist Mike Waters walks on screen. This shot is a static, barren, and intentionally uninteresting composition, emphasizing the pure solitude of this specific Idaho road. Before we even hear the character speak, we know there’s a connection between him and his natural landscape. He’s on the edges of society, literally. Also, it’s interesting to note his clothes at the beginning – I didn’t notice it on my first watch, but after several watches I realized that his shirt says “Bob,” very clearly a hand-me-down from the eponymous leader of the Portland hustlers.

In this scene, he’s dressed in all blue: a natural color, resembling both the light shade of the sky with his shirt and the rich darkness of the river (no pun intended) with his coat.

Shots of the sky and the sea soon follow during the intro as Cattle Call by Eddie Arnold plays. This juxtaposition between the sky, reaching an upward limit, and the sea, reaching the vast downward unknown, perfectly sums up Mike as a character: he is both the sky and the sea, simultaneously reaching for a hopeful goal above, into the heavens, but haunted by what lurks beneath the surface — a past of trauma and abuse that he can’t shake, and the mortifying fear of resurfacing unfulfilled dreams. He dreams, but doesn’t expect anything.

Both the sky and the sea are elements of nature, though, and they represent the reality of the human soul. Whether it's the idealism of the atmosphere (“the sky’s the limit”) or the depth of the ocean beneath the surface, those feelings are still real feelings of humanity. The darkness can still feel fulfilling, because it’s real.

Also — Mike’s last name is Waters, and he is played by River Phoenix. While the film doesn’t necessarily center bodies of water in the cinematography, the main character is unbreakable with the sea. He travels across an ocean in order to look for his mother, with no luck. In fact, his initial “call to action” is the sound of the ocean through a client’s decorative conch shell, begging him to take a swim, to take that risk. In the end, the sea wins, and he’s pulled back into its depths.

Costuming My Own Private Idaho

In an analysis of costuming in this film, it would be remiss to not start with the most iconic fashion choice — Mike’s orange and yellow coat.

In the Portland scenes and for most of the movie, Mike is dressed in primarily the colors orange, yellow, red, and brown, with neutral colors like black and white supporting the ensemble. These colors evoke the season autumn, with the image of the leaves falling from the trees. It’s important to note that the film itself takes place in fall, as you can see the leaves on the ground during the shots of Portland with Mike and Scott.

Especially since he wears this outfit in an urban area, it visually connects him among the few traces of nature in such a stone-like concrete city — the dead leaves. He still retains his humanity, and expresses this innate connection with nature through his fashion. Unlike the rich colors of the opening shots, the Portland section is cold and devoid of any color. Mike’s clothes are remarkably vivid in hue though, and his innate humanity throughout the film makes him stand out; despite his conditions, he still believes in something, even if he doesn’t know what. And most importantly, he’s grounded in his self-identity. He knows who he is, and his clothes show how he truly is connected to both the natural world, and his own inner world.

But, if Mike's naturalistic clothes reflect his humanity, then what could be said about Scott Favor’s cold, neutral suits?

Scrutinizing Scott Favor

During the Portland block of the movie, Scott Favor stands out in a number of ways, but perhaps the most visually obvious is the fact that he prances around in well-kept black and white suits, complete with waistcoats and polished shoes, while the rest of the characters wear torn-up rags. Not only does it show Scott’s dissonance from the homeless street hustlers he placed himself among, but it also paints him in unison with the concrete jungle he resides in. He is, by innate connotation, a man of society. He’s what society values in men – both rugged and polished, confident and (presumably) self-assured, arrogant and ambitious, but most importantly: wealthy and heterosexual.

It’s all fake though. Like a city, he’s manufactured: it’s not his own self expression the way Mike’s clothes are, but it’s an expensive, easily replaceable suit. There is no color, no personality. He’s alien from his homeless friends, but he appears either posh or edgy nonetheless, depending on the circumstances. In the city, his clothes are all generally black, white or gray.

Even when he meets his father in the iconic shirtless-black-jacket-kinky-choker outfit, its all just a “fuck you” to his dad, rather his true self. Even then, in his edgier outfits, he’s putting on a facade of anger to hide his sensitive side, the one that’s affected by all of his isolation. But nevertheless, when he’s in the city, this is the only reality he’s created for himself. He’s defined by his surroundings, he’s defined by his role in society, and the responsibility to be everything they want out of him. But unlike Mike, who sticks to his own humanity without ever conforming to the social model, Scott molds himself into a facade to present everything that society demands, suppressing his humanity under a three-piece suit.

But it’s very interesting to note how easily the reality he constructed for himself falls apart when he, like Mike, begins living on the edge of society: among nature. Note — he only really wears suits, leather, or neutral tones when he’s actually in a city, like Portland or Seattle. But, when he’s on the road with Mike, watch how his fashion changes: cherry lace-up boots, ripped but modest jeans, an orange and blue shirt, and a mocha jacket. Remind you of anyone?

He’s neither the three-piece suit or the leather dog-collar: this is who he truly is. He’s individual and alternative, but still not completely edgy; he’s masculine, but soft.

It’s interesting casting Keanu Reeves in a role like this. He’s not the vision of a typical American hero — he’s handsome, but he’s soft: his vocal delivery is gentle, his muscles are defined yet softened at the edges, and his face, while often devolving into a blank stare at times, is youthful and polite in this movie. It becomes, then, who Scott Favor is, and his outfit with Mike reflects that unique soft-butch air that Keanu Reeves brings to the role.

The tone of his outfit changes with the tone of his character: during his journey with Mike, he genuinely loves him and sticks with him for as long as possible. He battles with a conflict, a constant tug-of-war in his character that breaks near the end: a balance between sticking with his plan, chasing money and fatherly approval, or being human, being himself, and being there for his friend. He knows he’ll have to leave Mike at the end of their trip, but for the journey, he’ll stick with him.

Thus, his natural tones during the midsection of the film reflect the true, if brief, humanity that thrives buried in him. During the journey, he’s brought to a physically natural and isolated place, on the edge of society. It’s here he can truly be himself. He’s away from his high-society family, his father’s expectations, the capitalist mentality of constant wealth accumulation — the place that reminds him of who he’s supposed to be & everything he’s not.

He gets to live like Mike for a little bit while they travel, which is reflected in the fact that he and Mike share similar-toned clothing. However, he ultimately fails to accept himself the way Mike does, which is why he reverts back to his three-piece suit at the end of the film. This is his first time really on the road alone with his humanity, and it allows him to discover who he truly is, especially in regards to his sexuality.

In the natural world, on the road, he’s able to reflect on who he truly is. And that terrifies him to his core.

A Story of Unrequited Love?

It’s 2024. I think we can all agree that Scott Favor is gay.

Despite ardently refuting it during the famous campfire scene, the subtext almost confirms his homosexuality. The poignant words, “I only have sex with a guy for money,” juxtaposes two things in the nature of their lives: sexual intimacy and wealth. They commodify their bodies by the nature of their jobs, as they sell sex for money.

For Mike, money is survival. For Scott, money is added wealth. He’s quite literally not in it for the money, because as Mike points out, he’s got money. Scott says that he needs to get back at his dad, and begins the campfire scene with the famous story of how he told his maid, “wherever, whatever, have a nice day” when he left home.

But while this is true, it’s not the whole truth. He’s becoming a prostitute to get back at his dad, but for what, exactly? Part of the answer can be because it allows him to explore his sexuality with men, a fact that his father almost certainly doesn’t approve of.

But, there’s a catch. The problem with exploring his homosexuality solely through sex work lies directly in the soulless capitalistic nature of work. Scott only experiences meaningless sex when he’s working, because he’s still driven by an invisible, unshakable desire to generate wealth, even indirectly.

The other part of the answer is that it lets him pose as a “fuck-up” so that later he’ll surprise everyone with his sudden change, and he’ll generate the most wealth. Everything about Scott is temporary; he’ll have sex with men temporarily, and he’ll care for his friend temporarily. It’s in his name — he’s providing a “Favor,” if you will, to others — but only for a while. Then, it’s his turn to receive the Favor. It’s all the in-betweens that lead up to his final, grand vision. He wants money, but it’s not just about the money. Ideally, what he wants is acceptance. He wants to be loved for who he is by the people who he grew up with. He doesn’t want to always live marginalized, but he does revel in the freedom he gets when he does live there.

And then, there is of course, the famous campfire scene, where Scott proclaims that “two guys can’t love each other.” The way Keanu Reeves delivers this line sounds both soft and forceful, yet unsure. He never sounds rigid and angry in the conversation, but the way he delivers this specific line after a pause highlights how Scott is almost confused about what he’s saying: he doesn’t even know if it’s true, but it’s what must be true, right? This is what’s expected of him, isn’t it? It sounds forceful in that he’s spitting the words out, yes — but not to Mike.

In fact, this whole conversation has nothing to do with Mike, really, at least in Scott’s eyes. No, he’s really talking to himself when he says this. He’s reassuring himself: what I’m feeling isn’t real, because two guys can’t love each other.

He wants to love Mike. He really does. Never does he say “I don’t love you” or anything along those lines. No, he says two guys can’t love each other. They can’t. At least, not out there in society.

But he’s not in society. He’s in the titular Idaho desert, isolated miles and miles away from the concrete city, and the closest person he lets in is telling him, “I love you, and you don’t pay me.” Mike says that money isn’t important to him. Unlike Scott, he is not driven by the desire for wealth, and further, societal approval. Scott hates his humanity because it conflicts with his society. Mike only has his humanity and nothing else, because it was all taken away from him by society. “I love you, and you don’t pay me” is such a powerful line because it deconstructs everything Scott’s ever known. Mike revolts against America, against society, against capitalism, with that one line. He doesn’t just not need money, he doesn’t want money. It’s an unashamed declaration of his love that rejects all the constructs of wealth and monetary reward — that rejects everything Scott has ever known.

Mike is a disabled gay man who never fit into society, and Scott is a wealthy gay man who was manufactured by it. He was forced to bury his humanity, his love, while Mike clings to it like a weapon. Mike’s sexuality and the love he has to give is the only thing that society can never take from him. But, the cult of wealth has already taken Scott’s identity, always letting him know that if they only knew, he could never return.

The I love you, and you don’t pay me line is what scares Scotts into retreating: it is here he understands that his love and his society are incompatible. It’s an I love you that’s despite money. Scott understands that he can’t ever be what’s expected of him, and he’s afraid of giving up everything he’s ever known and wanted. He’s dug himself so deep into the mindset that he can’t imagine a world where he loves himself.

(Here’s a track that I feel sums up my thematic reading of the film. Gotta love Mitski!)

On Sex and Sexuality

And as the film concludes in its final act, Scott continues to retreat further back into the constructed falseness of conforming to societal expectations. Back to the topic of sex, Scott has sex on screen with Carmella. But, the sex with his girlfriend is, interestingly, shot the exact same way as the sex with his clients: in robotic, emotionless, photographic stills. He’s on a mission, completing a task the same way he would for work. It lacks the full passion that he desires in sex; by this point, he knows he doesn’t love Carmella, but it’s too late in his plans to change his mind. He needs to finish what he started, and that means marrying Carmella and collecting his inheritance. It means winning the American Dream.

By the end of the movie, Keanu Reeves portrays a war-like Scott Favor in his three piece suit, a battle-armor that allows him to feel like he belongs, even when he doesn’t. When he’s in the restaurant and talks back to Bob, he is stiff, stiffer than ever before, and seems conflicted. It’s like he’s forgotten how to smile.

Scott engages with sex a few times when he’s on camera, but it’s interesting to show that whenever he’s in a sexual situation with Mike, he seems to genuinely enjoy it, even if it’s not necessarily real. The scene earlier in the story where Scott and Mike fool around in bed to ward off the men his father sent feels real. And even throughout the whole film, the only time sex seems real in this movie is whenever Mike perceives it.

For instance, let’s look at the first real scene of the plot, when Mike receives that blowjob from a client. It’s a moment that’s real to him, and it’s uncomfortably real for the audience, too. But the way he perceives sex in other people is also very real to him. Much later, when he’s trying to sleep in Italy, he hears the breaths and moans of Scott and Carmella having sex in the room next door. We’ve seen the way Scott perceives the sex — quiet, barren and unfulfilling — but Mike feels it in its entirety, or at least, he feels Scott in his entirety. Again, this illustrates his innate humanity: he’s connected to the emotional aspect of sex, and everything he feels becomes real.

By the end, Scott has essentially subjected his marriage to a bleak, static sexual life that will forever be out of touch with his true self. He’s won the American Dream, but he’s lost his integrity. And in this way, loving became his biggest resentment.

The Ending

When Scott sees Mike on the other side of that field, his expression is blank, but by no means unaffected. Mike, ever the lively, isn’t upset at Scott either. It’s like the two have a communication between them. Mike of course hates what Scott did to him, but he peers back, knowing he’s unhappy. Scott looks on with a subdued envy. He shouldn't be looking, but he can’t help but watch. He’s by no means angry in his gaze, but it’s a gaze of peering into something.

In this moment, Scott reflects on how truly unhappy he is. He sees Mike shouting like Scott himself at the funeral, the same way he would shout atop the abandoned Portland buildings. He can’t shout like that anymore, because he’s given in to his own prison. Scott has killed himself and sold his soul. It’s all Mike has, but it’s what Scott gave up. Scott has lost.

The ending of the film leaves more questions than answers, but if the man truly is Scott (a fact corroborated by the original intentions for the script book), then it shows how there’s still hope in him after all. But the choice to leave the ending vague and open to interpretation drives home the uncertainty of these characters’ lives: what can they do now, besides reflect on the whirlwind of their recent expedition?

In nature, Scott learned infinite truths about himself, but he lets the fear of societal rejection push him back into his material world. But, the space he enters in the Idaho desert is the very concept of a “Private Idaho”: the place where he can be himself, without judgment from the rest of the world. A Private Idaho is the feeling of being seen, of being understood, of being true to one’s own self. It’s the human element, a campfire if you will, that never burns out. It’s the hunger for more, for openly choosing love over wealth. A Private Idaho is away from the constraints of society, a place where the characters can either choose to love, or choose to run.

The story My Own Private Idaho is the story of one’s journey of self acceptance: it’s the tale of a character who lives in his own private Idaho, and a character who’s haunted by his own private Idaho.

I was really intrigued when you touched on how intimate actions are mostly robotic and manufactured with Scott, and how they become 'real' when Mike perceives it. I also enjoyed your costuming analysis. I watched the film a while ago and I had the gist and the idea that Scott and Mike represented opposite ends of a spectrum, but to see it laid out like this in text really helped me comprehend the film on a new level :).

this is suuuuuch a great read!! tysm